Interesting to go for a run during rush hour only to realize that the whole city is keeping pace.

The same goes for childhood passions; discovering overnight that everyone else seems to share such an intimate moment as playing a Pokémon game on the Nintendo DS through its reemergence in the mass culture under the guise of Pokémon Go in 2016… Weird.

I’m not writing an essay here longing for that moment, — of course not, 2016 was too strange a time to yearn back for,— but Pokémon Go and Niantic Labs are back in the news in our similarly strange year 2024, and I wanted to touch on that app and its consequences because I think it’s important to grapple the Pokémon Go moment, especially speaking now as someone for whom the Pokémon games were sooooo important having spent hours and hours in the back seat during cross country car trips as a kid.

Thinking now of the names: Charmander, Bulbasaur, Squirtle, Pikachu, Eevee, etc…

Pokémon is fun, it really is. Or it was, at least. Here’s a legacy franchise that keeps itself somewhat fresh on the novelty and poetry of these little individual linguistic, design-oriented creations. Could you imagine a more fun gig than creating Pokémon? Like the names? You could make a turtle with a cabbage on its back.

Oh wait.

I know as well as you do, it’d be lying to say it wouldn’t be the best job ever to have made this guy.

Anyways, all jokes aside, such a small eye-catching node like trading cards, with names like pocket-sized poems evoking that feeling of sweeping zoologic grandeur that came along with realizing the very real existence of dinosaurs as a small child, thus unlocking a vague realization of how vast Earth’s history actually is, are awesome, — I can’t think of any other eye-catching pop-culture nodes that could stir such a passionate childhood feeling. It’s the pure beating core memory of online fandom cultures, I suppose.

The Pokémon Go Moment

In the week when Pokémon Go dropped on the App Store, it was downloaded more times than any other app in history. This success was, in a word, unprecedented. I’m thinking now of Hillary Clinton’s line “Pokémon Go… to the polls!”, during her ill-fated presidential run in 2016. It’s funny in hindsight. She said that because polling data and Google Analytics told her campaigning team it was so big not to mention.

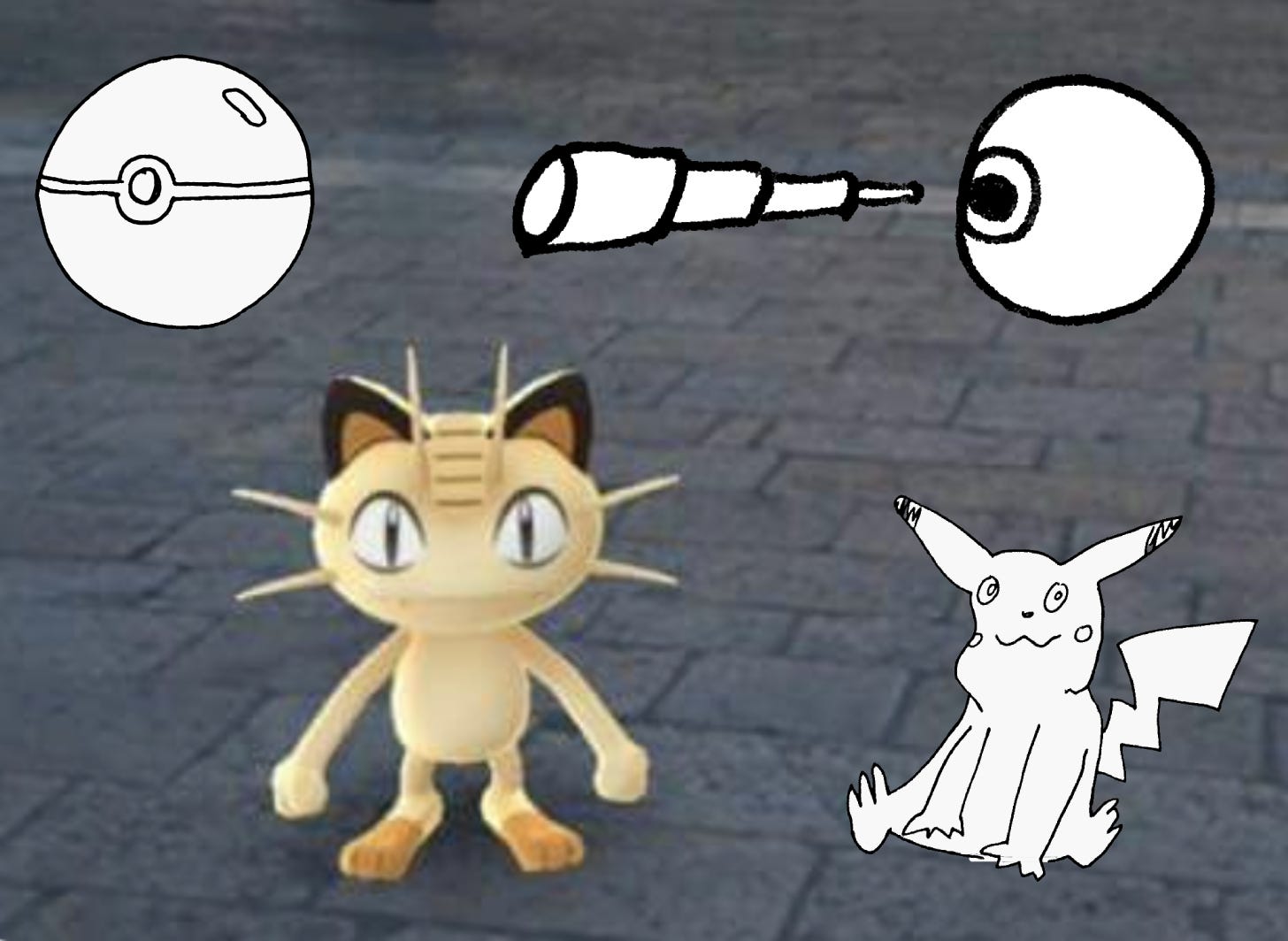

Unprecedented, too, was the app’s depth of data collection,—to play the game, to sling red-and-white balls at wild animals after you’ve beat them up outside of gas stations, the user is demanded to give uninterrupted use of their location and their cameras. Anywhere they went, any picture they took, any mere framing of your lens on anything at all, everything could be snatched up by Niantic Labs’s data bank and distributed to various tech companies and defense contractors … And certainly it all was. That’s the unfortunate fact.

As a part of that generational moment, — very symbolic of the rampant exploitation of fandom nostalgia for the sake of surveillance capital, — it’s an interesting thought to linger on considering just how many small personal moments of everyday lives are archived in a company like Niantic Labs’s databanks: how many birthday candles blown out, how many concerts photographed, how many wedding photos, how many first newborn photos, etc.

John Hanke (never trust a man with a handkerchief name)

Ninantic Labs’s CEO at the time, John Hanke, had just come fresh off from his tenure running Google’s Geo division. His CIA-funded company, Keyhole, was acquired by Google in 2004, made into Google Earth, and such a project is and should remain mortifying for anyone hoping to retain a separation between the real and the digital because, like anything Google does, the project is not towards the betterment of humanity but to the increasing of Google’s annual revenue.

The first real scandal that rocked Hanke was the so-called “Wi-Spy scandal”, coming down around Hanke once it was discovered by the German data protection commissioner that Google Earth’s camera-clad vehicles had been illegally collecting Wi-Fi data from almost every router they passed by, as if Google quite literally owned the rights to the entire internet. Certainly this invasion of privacy should not go unheeded when considering many of the same people were involved in Pokémon Go and still structure the world today.

Pokémon Go in 2020, Smart Cities

Moving on now to 2020, Niantic Labs acquired AR company 6D.ai and posted about their goal to recreate the world in an Artificial Reality mold.

Here’s this quote from Artificial Reality Pioneering Australian Guy Mark Pesce on Augmented Reality: “by virtue of the way they operate, augmented reality systems must simultaneously act as a very sophisticated surveillance system.”

This fact of Augmented Reality ties neatly into the idea of a “Smart City,” a notion which means nothing to anyone really, except for the city’s police force and a handful of people who want to sell localized advertising metrics.

The idea of a smart city, performed by companies like Palantir, is to partner with local Law Enforcement and to have an eye-in-the-sky view of a city, collect all the available information about it to maximize its security, to know where people go, what they do, but never why they do it, to string together what is and what isn’t, by all means it’s a proper surveillance system. I have strange trouble in really realizing this… because what changes if I do?

And unfortunately, every time you go to catch a Pokémon, those wonderful little sigils of a childhood nostalgia, you’re adding a piece to the puzzle of such a surveillance system because the footage you take when filming yourself throwing Pokéballs at a Snorlax in a Starbucks is added to all of the other footage taken inside the Starbucks, as to map out the space and to sell that map. And you must realize, this isn’t because Niantic has a pressing want for mapping out individual Starbucks storefronts but rather because Niantic wants to map out every interior space it can. This sort of mapping out of reality is a self-reinforcing cycle too, because people follow the app to where it leads even if it leads into a concentration camp.

That interior data is being sold to the highest bidder, which will, in the United States, almost always inevitably be the surveillance wing of the twenty-first century’s Big Bad, the Transatlantic Military-Industrial complex .

Now let’s enter the AI era, because of course it’s a natural next step for Niantic Labs to be gung ho about developing a “large geospatial model to achieve spatial intelligence.” This sort of jargon just indicates that it’s helping to develop a model for AI to navigate the real world outside of what’s accessible by cars, therefore outside Google Maps’ already hefty collection of numbers and figures from the real world accessible by car.

Algorithms which are created from data collection increasingly informs our daily lives; year after year, they are less of a mere “technological progress,” and more of a straight jacket being sewn together string-by-string while our arms remain motionlessly crossed at our chest.

It’s important to realize these algorithms are structured for profit. These algorithms structuring our understanding of reality are, by all means, the modern Wall Street ethos yearning to become realized fully, and this geographic contact tracing is a genuine part of capitalism’s ascendency over our ideas of reality, — the project, of course, is to make it completely unthinkable (unfathomable!) to imagine anything outside the logic of data collection.

We have to realize that these new dominating powers are not going to be 1984-style Big Brothers that come in to your apartment and electrecute you into submission, — not to say they don’t already do those things in the poor parts of the world, — but rather it’s going to be through our gradual acceptance of what Palantir, Google, and Niantic Labs are doing in their general projects of placing reality on rails.

Let’s talk about the Drone Strikes of it all

I still genuinely believe that the big reveal of the dark underbelly of these sorts of data collection/analytics tech companies that have begun to own the world in the muddled haze of the late 2010s, and what is likely to come out from it, is the IDF’s genocide of the Palestinian people, the way in which this genocide is being perpetrated, the carelessness of drones and targeting done through generative systems, location tracking, and physical mapping of space.

Okay so first off, the IDF’s “kill list” is generated by Palantir’s generative AI, which, based on how shoddy most AI systems are in our year 2024, should be absolutely terrifying to anyone who has said one or two things online or in text messages that could be taken out of context by an AI that scrubs all of it and tells a military force which doesn’t quite consider your type of person as a full person that you might oppose them in some way.

That’s to say, there doesn’t seem to be much of a care as to whether this list is accurate or not. The IDF seems to be killing whoever whenever. The data analytics only gives them an excuse to do so.

And the killing itself, the targeting of the drones, is done through Google maps, more or less assisted by a handful of other geographic data conglomerators like those “large geospatial models” which Niantic Labs develops. Again, it’s not like the IDF cares too much whether these models are accurate, only that they’re efficient.

All this is to say, the data being gathered up by these companies will be used to perpetrate mass, mechanized killings. They are right now. They will continue to be used this way.

And don’t let yourself fall into the thought, as an American, that these problems are an ocean away. Certainly there were people playing Pokémon Go in Palestine in 2016, I would be very surprised if there wasn’t a single Raichu caught in Gaza, and certainly the data collected from those videos and swipes have been used somewhere in the masses of data used to inform these systems.

And to tie it back home, the relationship between the IDF and American Law Enforcement goes deep. American and European police chiefs who schedule the training of officers often have them train with the IDF, and besides that, there are countless cross-atlantic trades being done of arms, supplies, data, and methods of warfare/supression between the IDF and the American police. The American Law Enforcement playbook is borrowed directly from the IDF’s; that should be a telling reminder of where we’re going and why we might need to seriously consider protecting our data.

But, like…

We don’t have to let these forces of algorithmic control over reality to take away from what we hold closely to as part of our childhood. Go ahead, pirate yourself a copy of those classic Pokémon games you used to play, — stick it to Nintendo for partnering with such diabolical forces, get yourself an emulator and relive those experiences if you care to. I’ve done it. It’s fun to go back to in small doses.

And the Pokémon cards buried in the dark cellar of my mother’s house will always remain shimmering under the light of my recollection. Just because their symbols, — innocent mascots to cover up a datafication of the world for the sake of the powerful, — have been used to perpetrate this crime, there’s no need to feel ashamed of anything. We got got, sure. But we can learn that lesson, I believe. At least we didn’t get duped quite as bad we did with Harry Potter when JK Rowling came out as a world-class bigot.

~Links~

“Privacy Scandal Haunts Pokémon Go’s CEO” — The Intercept

“Pokémon Go wants to make 3D scans of the whole world for ‘planet-scale augmented reality experiences’. Is that good?” — The Conversation

“Pokémon Go Players Have Unwittingly Trained AI to Navigate the World” — 404 Media

“Pokémon at the Titty Bar” — Exhausted, but Alive.

feeling a lil protective of bean head pikachu

only in a griffin post do we go from pokémon sketches to hillary’s flop marketing to palantir and IDF in a natural progression