Thanks for reading How to get to new york season 2, brought to you by this laptop here and a couple dozen cups of coffee some of which were piping hot and most of which were forgotten at my desk for probably too long. If you want to read more from the series, including last season’s efforts (from Summer/Fall 2024), you can find it in full here.

The times don’t make a person but they can reveal them. A mirror on the wall in passing is a formidable encounter for anyone to come face to face with as it’s made up of the same bitter stuff recollection now uses to buff up the horizons around memory — glass is always as alluring as it is a threat. I can’t help but notice my own reflection in the screen as I write this, I can’t escape it. Is it right for our reflection to be everywhere we look? Mirrors and phone screens, one for the present, one for the past; we’re in a glass century, looking at ourselves, now and then, forever.

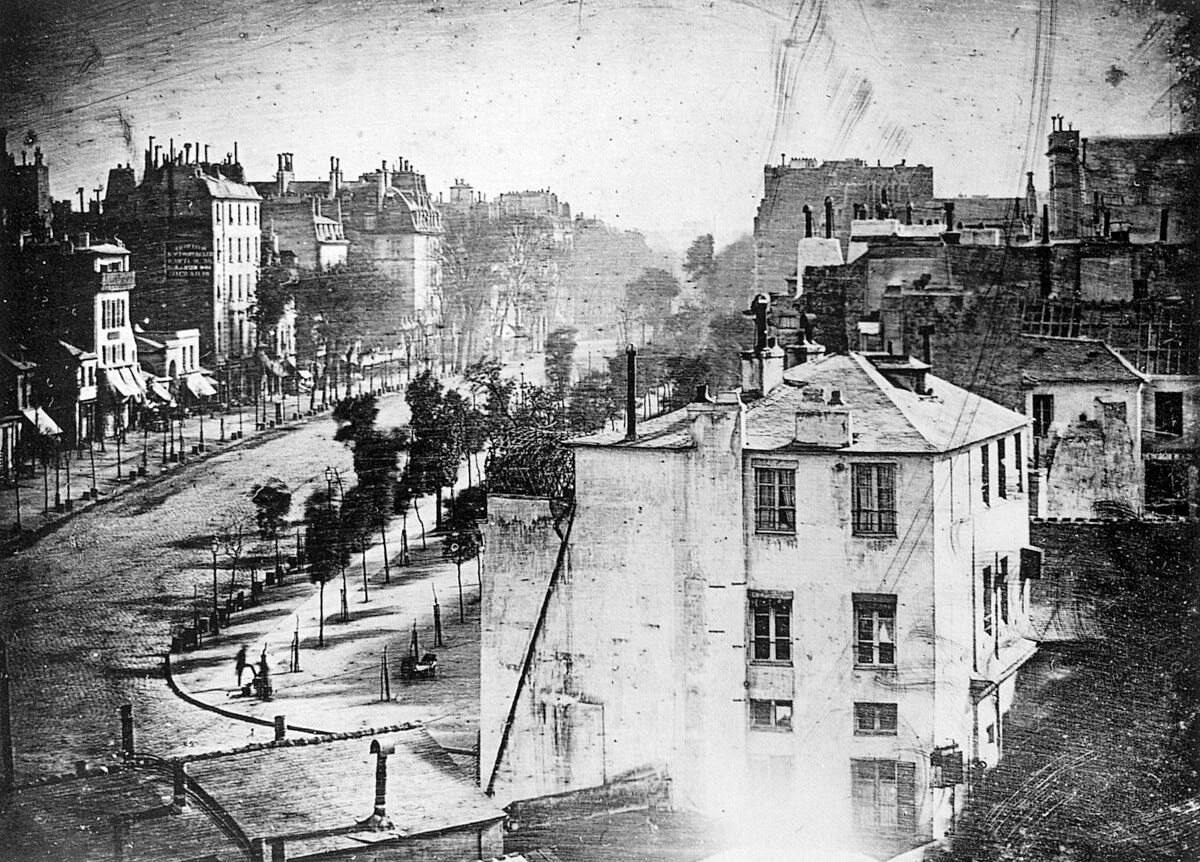

Context is so simple yet so hard to place in the depths of a camera roll. The context remains murky like a name or a face you can’t quite place to a who, when, or where. A snapshot taken and captured doesn’t carry along its context. Any photograph, like the one above for example, has been picked up and put down, in a personal regard, so many times since it was taken and it will remain where I need it if I ever might need to refresh the memory, unravel the moment, lend light to a time not too terribly far back.

I remember who I was back then — I can’t help compare my recollection of the who to who and what I am now — and the photo helps in this, lends a hand, commemorates a single moment in time before the canyon of the pandemic ushered in the twenty-first century, proper. This is nice. I like this. I existed before. And unless you’re six years old or under, you existed then too.

But, looking at it now… Is the above picture even true? Is it doctored? Generated? Edited? I’ve developed a tic when looking at any photographs wherein my eyes do a sweep for all the tells that might indicate generative AI. Is that me, there, on the far left, or is it someone else? It it someone who only exists in pixels and one chemical copy glued down in my friend’s personal moleskin? I was twenty then; I’m twenty-five now, feeling like a Ship of Theseus, and it is true that my molecules have been replaced one by one over the years but these even with these changed eyes I can recognize these faces on my screen, I can read them from left to right like a handwritten letter to myself from five years ago.

I’m now reminded of the first photograph ever taken of a living person. Louis Daguerre, inventor of the daguerreotype and also, in general, the reason for daguerreotype being such a hard word to spell, took two pictures from the window of his Paris studio in 1838 with this machine he had just assembled out of metal and chemical parts. The first take was of the city early in the morning; the second in the afternoon. These pictures took in light for around four minutes, four minutes of exposure time, creating a long enough pause between the start and finish of the chemical process of capturing that most of the city life becomes removed and ghostly due to its movement. But in the afternoon daguerreotype, two figures happened to remain somewhat still throughout the entire four minutes, two unknowns who would forever be captured in two-dimensional resin, two unknowns spending an unassuming four minutes on Earth that would be made infinite. They would remain in place for centuries, without their knowing or even comprehension. You can see them now below, near the bottom left corner. One stands with one leg raised. The other sits.

And I can’t help myself from trying to imagine what they talked about, what their lives had been like, what their relationships were to one another. Old photographs and daguerreotypes fascinate me endlessly. I can’t help but wonder. Were there others? Was there anyone else involved with these two made invisible because they had been in motion? — If there were, certainly they’ve escaped the tree sap of a camera that Daguerre had created.

We’re not so lucky in our own time here on Earth to be so oblivious of our own images and outlines as they’re taken up by mechanical systems of representation and depiction, a process that hangs forever just beyond our comprehension. We’re stuck in perpetual, back-lit amber, thinking to ourselves this is fine, thinking to ourselves this is how things are. And they are like this; and they’re most likely fine.

The photo at the start of this piece, with the distortions of light feeling appropriate to the time and conditions of our lives at the time, was taken in January of 2020, just over five years ago, on my friend’s 30mm camera. I remember the date well — January 26th — because Kobe Bryant’s helicopter had crashed right before we took a heavy dose of shrooms blended together with orange juice, banana slices, and frozen berries, all of us sitting around a coffee table on a Friday near the end of Winter Break in the loft space that our secret ninth roommate, who I’ll refer to here as L— , would soon enough make into his bedroom and later his aviary.

The lot of us had been roommates for eight months — it was a tentative agreement between people who knew each other through the dorms, through classes, and through facebook marketplace, a typical case of student housing — but soon enough, two months later, the pandemic lockdown would begin across the continental United States and we would be locked in together for almost two years.

Last night, back to present, in 2025, mumbling and curving, a projector screen was pulled down across the tarp of my skull and a small troupe of character actors from the 1960s, all wearing low budget cowboy outfits, put on a series of skits, scenes from box office hits, sung karaoke, acted out one act plays, and on occasion drew out long pauses and held tense narrowed eye-contact with another, fingers twitching near the triggers of plastic guns. After the movie was done and finished — the Criterion Channel is a blessing, isn’t it? — I went to bed and I dreamt I was living in Madison, Wisconsin again.

This was my own damn fault. Hazy-headed and kind of stupid a couple nights before, on the way home from the bar, a little drunk but not severely, I had scrolled down into my photo roll. I saw people I once knew, people I don’t know anymore, saw parties I attended, saw parties I’ve since forgotten, saw people I dated, saw people I’ve not spoken to since, saw people I ran away from and ran towards, saw friends of friends whose names I’ve forgotten and friends of friends whose name I remembered better than their faces. Notice, now, the sheer number of “I”s above, strewn across this paragraph. The “I”s remind me of a dark forest made up of solitary trees casting shadows of what-if imaginaries across the dark of this post. It’s funny to have so many pictures of myself in my phone of who I was then, and pictures of the people who’ve shaped me into who I am now.

A photo roll grown long over the years is a sawmill that never ends. These moments of connection, screenshots saved to text a friend and all the rest of the photos I’ve had reason to take and save will eventually sever from their retrievable, rememberable context. It would be an oxymoron to claim experience can ever be fully preserved. Thankfully, though, a good photo roll is a productive saw mill. People come in and out. This isn’t any sort of dig, just the way a life lived exists in a modern, interconnected context. We meet, we leave. Repeat.

But it feels like a shock to the system, doesn’t it? The leaving and returning. The sound of a saw splitting a length of wood is only ever going to be a loud cracking noise, especially in memory. And I feel trapped in this cycle. Meeting new people, drifting apart. Such is the plight of the graduate, I suppose. I’m as aimless as they come. Such is maybe also just the curse of being in my mid-twenties during the century’s mid-twenties. Stars align and everything feels significant when no one knows what to do next, which direction to start walking.

In the dream brought on by my tangle with my photo app, I woke up nineteen again, on the cusp of adulthood. I suspect the last step of our teenage years is a hazy time for most of us. We can imagine a blooming social life on the horizon, something like a sunrise, just past the bar where you and your circle can sometimes manage to sneak past the bouncer. Nothing much happened in the dream. I just happened to be in the bedroom of the house we lived in on North Bedford Street, a house with holes in the walls and peeling paint and duct-taped carpets. This house in particular:

Upon waking from the dream, the long-held desire to be young enough to make better, more correct decisions was no longer with me for the first time in years.

Such a desire has been a phantom that I shook hands with and watched leave the room. It had evaporated somewhere along the way of my waking up like the sun blasting away the morning dew. To go back in time, to redo things… I don’t talk about this terribly much in person but I suspect I write about it to death here on this blog, that my life, like any real modern life, has been a sporadic series of meetings and leavings.

I become a new person every two-year period and then, the next two years I spend in the trenches of embarrassment at the person I was last, the person I worry I’m becoming again for no reason other than “that was who I was two years ago” and merely having been someone is warrant enough for embarrassment, it seems for me, deep down. Personality is branding. But god, do I hate branding. The contradictions only grow out from there.

Anyways, by twenty-five, there’s a lot of thread to work with in this great yarn of recollection. One has to knit the memories out to make anything coherent out of them. Maybe a scarf? After all, Jung writes that a person doesn’t reach adulthood until they hit twenty-five and twenty-five is around the time I finally started to wear a scarf in the wintertime.

But adulthood is oftentimes too messy to make coherent, to straighten out. It’s too messy to focus fully on the act of knitting. Whether or not you can save those memories and feelings only depends on how well you can knit with a keyboard, how realistically you can flesh out the memories. Such is the use of an old photograph. And with old photographs, melancholy is a marble that grows in your mattress and if you try removing it, you have to look at it dead on, you catch a glimpse of yourself in its reflection, and that is a hard road to walk back along.

I have always been stupid in my own ways; reverting back to myself nineteen would be like money changing between hands. I simply wouldn’t know what to do with myself if I wasn’t who I am today. Fantastical thinking gets one nowhere. I like to think I would have a more clear-headed understanding of what this life would look like, where I’m coming from and where I’m going, but there’s no assurances that my nineteen year old brain wouldn’t just revert back to whatever piddling distraction it would have been on anyways. And I wouldn’t want to go through that loneliness again, and I wouldn’t want to relive the pandemic.

The pandemic was what appeared to be a rock thrown through the window of our house and it wasn’t until a week or two passed that we realized it had been thrown the window of every house.

The pandemic is the rupture I’m talking about in this piece (with its ominous title). It was the great rupture of everything social in our lives, we could almost feel the earthquaking below our feet. I’m constantly surprised that the pandemic is talked about so little. It was an event which (permanently?) changed our worldviews, defined our era, thrust us into a strange portal of desensitivity and unreality where we now float in a suspended animation. I think the reason no one speaks of it outside a muted whisper is that there’s no need to acknowledge it. Millions of people died. The social structures across the world imploded. These are things we feel. Speaking about all of it would make it almost feel as if we were doomed from the start, by the time and place of our birth, to exist inside a dead photograph of the world in the process of changing towards something more inhuman than even the industrial revolution.

The international system of communication and trade emerged as a real, living, breathing thing frankensteined into horrible life during the pandemic. And I think that’s reason enough for some more thoughts on it, written out and focused on. The idea of a “pandemic novel” has a lot of people rolling their eyes online, but why not? Should we not write about it? We could see the new world stomping outside our windows as we huddled inside and coveted our remaining toilet paper rolls, and we scoff at the mere thought of talking about it?

But the facts of my particular situation during the pandemic were good, maybe great. A lot of people had very bad times, a whole spectrum of very bad times were had. I’m thankful for my privilege, I guess. I was twenty and living in a walkable city with weather just fine enough in the summer and shoulder seasons to spend most of each and every day sitting outside, sipping coffee, throwing darts at cans of light beer, sitting in lawn chairs, reading on rooftops, smoking on balconies, etc. The indie bands in Madison were great, are great, and will forever be great (check out Disq if you haven’t). The food is cheap and carb forward. The bars are all quaint and reasonably priced. Two lakes, multiple parks in walking distance, many nature trails, hidden public docks (and sometimes private docks) out onto the water (if you know where to find them, at least), bike trails, hidden DIY venues, monstrous sprawling student houses more like playgrounds than anywhere fit for someone to live. What a place to go to college during the lockdown! And between, a midwestern summer crisp like an apple. You could almost taste it. I could feel the ground beneath my feet as I walked. The trees in Madison have a beauty like nowhere else.

But a morning that is still a morning after three weeks of morning, and then still morning after two months of morning, and eventually, still morning after two years of morning, time becomes changed. Everything settles into a strange, strangled routine. Relationships with people outside of the house become furniture. The expectation is safe stagnation. A staleness unfolds. But then a football explodes in the street outside the window, run over by a 2020 Jeep Cherokee driven by the assholes down the street with a trump 2020 flag in every street-facing window. Things were dull and quiet until they weren’t. And when they weren’t, I became reminded that the world was nosediving into something strange and alien.

Again, I don’t mean to say my circumstances were’t good: A lot of my pandemic involved laying on the floor and staring at the ceiling, or at a book, or at the wall. I’m maybe a rare case but these are things I love to do. Perhaps the things I’m best at. I discovered spirituality, Borges, and LSD around this time and, just like the hippies seeing UFOs in the skies, blinking their eyes, and mistaking the blaring lights of postmodernity for extraterrestrial visitors, I began to notice the webs of soft power in the world — conspiracies having come to light, talking here about Jeffery Epstein’s downfall, the murder of George Floyd, a discovery of left-wing politics through readings and through podcasts, conflated with suspicions and hunches about Amazon services and mask mandates (and the protests against them) and the new centers of power. I feel lucky for having gone through this discovery in such an environment, one in which I could actually talk to a bunch of different people whom I lived with about different things. I was never completely relegated to a chat forum or group chat like so many other people I know. For this, I’m still thankful.

But that didn’t stop the ascendency of the unreal, the murky underbelly of what’s not being said asserting itself in a populist fervor like we haven’t seen since, probably, the 1930s. During the pandemic, the homes, apartments, rooms, dormitories, and townhouses, became incubators in which, almost as if the pandemic relief money worked as some sort of fertilizer or lubricant to bring the furniture to life. The objects surrounding us in our lived lives gradually came into a social dimension — our couch was now as friendly as a beloved coworker — and they spoke in their own voices.

The consumer economy has a fairly brief history. It didn’t really begin proper until the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s allowed for mass reproduction. But by the time the late twentieth century came around, objects became objectified so fully that they started to develop into something as living and breathing as the markets of stocks and bonds which undergird most of our modern lives.

Now objectification is complete and the mad doctor’s cries of IT’S ALIVE have faded so much so that people wonder whether there was really any mad doctor in the first place. Cars try and sell people on car insurance. Speakers ask the listener questions in automated voices. This was all alright when the ascension was happening, during the pandemic; it was nothing if not interesting to watch the first efforts silicon valley made at developing a proper internet of things but I thank god I had other people around me to talk to so I didn’t become subsumed by it. Thank god there was a small, rotund (cute word) cat wandering around the house clawing at closed doors. God, what a wonderful cat.

I could hear S— pacing back and forth in his room. I could hear him occasionally climb on top of his bed and jump for a couple minutes, maybe once every day during the middle of the academic day; I could hear A— listening to his Eagles podcast in the other room while he showered and brushed his teeth. I couldn’t hear either M— or E— from my bedroom. They were downstairs, but when I walked past their rooms I could feel bass vibrating the floor from their record players, the new Molchat Doma and Hop Along records, sometimes they were on the phone talking.

And little did the rental conglomerate we rented from know, L— was our secret ninth roommate. He slept in third floor’s loft, on the couch, and didn’t have a room to himself.

At the time, for some reason I can’t quite remember, I was scared of every single person in the building. This might just be a nineteen year old thing. I was terrified of other people, generally. At the same time I was barely securing rent, preferring not to eat food as a general rule of thumb. It is true that, when chronically hungry and unfed, everything appears more profound and spiritual in a way; but it is also true that long-term hunger makes a person fearful of others and themself. I felt like the lowest of lowlifes. I would wander out to the back porch to smoke or work out at the bench we had back there, the dumbbells gradually gathering rust, and I would wave at the neighbor in his balcony directly across from the gulf of gravel separating our run-down student rental houses from one another. I never got his name.

L— would come out with me to smoke sometimes and we would talk about things. He would tell me things that did make me worry a small bit, like how he contained a lot of anger and noise inside himself. He was unaware of where it came from or where it was going, he would say. “I’m not really sure what to do.”

In response I would say something stupid like “don’t we all, god, exam season” while thinking well it could be you’re sleeping on a couch and he would say nothing at all but he would look off into the distance, dejected and terrible.

It didn’t worry me. L— didn’t seem like he much anger in him, not to me, anyway. To me he was simply the guy who was sleeping on our couch. I brought this worrying moment up to one of my other roommates, S—, who had overheard one of these conversation from the kitchen sink when the window between the kitchen and the patio had been open. He was whittling a sharp point into a pink wooden paintbrush when I approached and he told me L—’s mother had died recently. I said “oh” quietly. The things people don’t tell you.

I then asked S— what he was doing with the now-sharpened paintbrush and he said he needed it to get the weed out of his one-hitter.

It was lucky for L— that we had two living rooms in the house: one on the first floor and one on the third. It was okay in a more unacknowledged way, for the rest of us living in 117 N Bedford, when he began to take steps towards shifting the upstairs living room into more of his own personal space.

More and more one of us would climb the stairs to the third floor’s living room to watch a movie, or watch an episode of some show on streaming, only to find L— standing on the couch for some unknowable reason, pacing back and forth, his hand on his chin. He would stand on the handrail of the back porch and joke about climbing to the spot on the roof where nobody had ever climbed before. While I began emerging from my own shell, he went deeper into his. He dyed his hair twice after he started dating a girl he met through one of the dating apps; they spent all their time together for three weeks, mostly at hers (as his bedroom was, remember, also our second living room), but I noticed, when he was at the house without her, he would become more and more quiet and anxious. He had begun simmering.

And when the relationship was over, his bleached hair frayed out into a dry feathery mess. He never acknowledged what had happened between him and her with any of us in any meaningful way, none of us knew whether he himself had done the dumping or if he was the dumpee. He began to grow quiet. He began to close the door to the living room for his own privacy and the rest of us began to steer clear, accepting that he’d just been through a lot and needed his space. The rotund little house cat wouldn’t stand for this afront to its domain, though. It was sit at the closed door for hours, mewing loudly, scratching the wood until its claws pulled out chunks. This all became much more dramatic when L— brought in his first pet bird to the unit.

The first bird L— bought was a small parakeet named Timothy. L— loved this bird dearly and to be fair it was a very sweet, maybe overly affectionate bird. We all tolerated the buildup of bird droppings in the third floor’s living room because there was a spark of light in L—’s eyes again and as the pandemic wore on, everyone began to develop their own coping strategies. I remember how the bird would perch on his shoulder and nip at his ears until he started laughing while, meanwhile, outside the house the pandemic changed in tenor and became more serious. We received news that UW Chancellor showed up at an “illegal” house party, a frail older woman riding along with the police and sternly scolding a group of shirtless, frankly wasted frat brothers for risking the spread of Covid-19, and we all became much more worried about our own little gatherings. If they were going after the rich kids certainly they wouldn’t hesitate to go after us too.

The spring began to become summer and the six-feet mandate felt more and more oppressive. We stopped inviting people over in general. One of the roommates more-or-less disappeared to a frat house for the entirety of the summer. The rest of us spent more time getting in the living room watching (and placing bets on) marble racing videos or Andrew Callaghan videos.

Amid this hazy anxiety, the rest of us were shocked to discover that L— had bought two more birds. They made loud squawks and flutterings throughout the day which we would sometimes have to apologize for, to the class in our laptops — “sorry about that, just my roommate’s pet bird.”

The two birds had been (1) another parakeet, a “companion” for Timothy and (2) a grey parrot named Merlin.

One time, not having been aware of these new birds, one of my other roommates had gone up to the loft to watch an episode of Nathan for You while L— was out of the house only to see what he thought was a bat hanging near the ceiling and he fled the space, barreling down the stairs and returning with a pillowcase and a baseball mitt only to realize that it wasn’t a bat at all but a massive grey parrot asking him if he had a cracker to spare. He didn’t.

I’m not sure, looking back, whether any of us interrogated L— very much on this newly amassed collection of birds. I think that, as the pandemic wore on, there was an increasing fear of confrontation, at least with real people who existed beyond a phone, and we all assumed L— was still very clearly rattled by his breakup even as the months went on. The best course of answer was to give him space. We could all use some space at the end of the day. And besides, he was paying a fraction of the rent. Besides, the birds weren’t becoming too much of an issue. Well… They weren’t until they became an issue around the time L— bought his first chicken, a large hen named Helen who boked and tored huge chunks out of the carpet.

Around this time the small rotund cat was going regularly berserk inn the hallway about the birds behind this closed door. It was howling and mewing and doing flips and tearing chunks at the door with its claws.

We asked L— about the chicken a couple nights after it arrived, as we had all heard it by this point. We brought up the topic of the chicken delicately with him.

“The chickens will lay eggs and it’ll all be worth it,” L— said.

“Chickens?”, asked M—. “Plural?”

And so the tensions began to rise quickly. Google ad services throughout the house began recommending pet-bird related products on all of our devices and platforms: feed, cages, nesting material, golden hoops, peg legs, etc. The sounds from L—’s bedroom were getting more erratic. He was keeping to himself for days on end. One of the roommates said he had smelled something cooking from L—’s bedroom and that it smelled like an omelette or something; — it was then theorized by the rest of us, in the group chat equivalent of a hushed whisper, that L— hada hot plate in his room and was living off of the eggs his chickens laid, presumably drinking rainwater and such. “How’s he using the bathroom, though?” I remember asking. I remember no one had any ideas.

The breaking point to all of this — another titular rupture — arrived on a Friday night. We played a drinking game in the second floor’s kitchen and L— was making a tremendous ruckus upstairs with his birds. He had around a dozen or so birds by this point. They would all gather around him and on him while he echoed their calls back to them, and they would echo back to him, and it went on like this for hours until until finally my roommate S— had had enough. He yelled something incomprehensible while he was aiming a ping pong ball at a red solo cup and threw the ball bouncing on the linoleum floor and stormed upstairs to the top room in the house with E— following close behind, pleading, “don’t mess with him man, just let him be, comeon.”

And when S— threw the door open and L— was standing inside, dumbstruck, wearing a crown of feathers on his head, laced through his hair, and large feathery wings were tied to his arms, himself speckled with bird droppings, S— really blew his shit, saying “fuck your birds. Look what they did to the carpet man. Look what’s becoming of you. This is out of hand man.”

The floor was covered in white droppings. The carpet was in shambles. The walls were stained. The room smelled insane. Oh god how will we explain this to the landlord, I remember thinking, distinctly, looking at the pile of eggshells stacked somewhat neatly in a milk crate. L— said “wha” and The birds fluttered off his shoulders to the far corners of the room.

S— walked to the window quickly and pulled it down, opening it to the night air. The birds saw their chance, as birds do, and launched out the window like a steady stream of water.

L— made a small, meager attempt to convince the birds to stay with him. But as all of the parakeets and chickens and the one parrot flew out the window, and as it became startlingly clear which way the wind was blowing here, L— began chasing after his fleeing mass of avian subjects with his arms spread wide like wings, as if he too were preparing for take-off, but instead of taking flight he crashed square into the latch, cracking his nose loudly, falling to the floor, face down, making a noise like a dying engine.

“God damn it,” said S—, looking between E— and I. We tried to pick him up but L— said “no, go away,” and refused to get up, continuing to lay face down on the floor.

There wasn’t a bird left in the room except for the large hen, Helen, who was in the corner hiding from the rotund little cat that was prowling the room with razor thin eyes, now finally in the kingdom of its desire. We kneeled next to L— and asked quietly if he was (um) if he was alright. He said he couldn’t stand up even if he wanted to. The paramedics arrived eventually and they checked his pulse, stuck a q-tip up his nose, and they scratched their chins through their face masks as the results came through and gazing around vaguely at the chaos in the room what with the bird droppings and the feathers and everything. They told L— eventually that his laying down here was of his own free will. Or it wasn’t covid-19, at least.

“It’s my own fault that my face is connected to this carpet?” L— asked the carpet.

“Yes,” the paramedics repeated, informing him there was nothing wrong with him but that there might have been some psychological misteps that could (and should, they clarified) be addressed under a therapist’s guidance. After the paramedics were gone, clearly somewhat startled by the farmhouse state of the living room, the rest of us turned L— over.

On his back now, still laying on the floor, his nose slightly purple at the bridge, L— transformed into something twisted and mangled, to be given away by his body language alone, a tortured soul in the shape of a person.

His light was fast extinguishing. We could all see it happening. Something dark and dangerous. A disaster. Someone had to stop this. Whatever heroes we had left to trust, their phones pinged and they were en route. The UW Chancellor urgently called the authorities telling them what was happening — certainly they were on their way. Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys were racing in. The Scooby Doo mystery team had just unmasked a villain, and the reveal pointed towards the direction of L— losing the world, or the world losing L—, and they were en route. Jack Reacher and Jack Ryan and all the Jacks from all the spy novels got in their paramilitary gear, ready to pull a nonlethal Seal Team Six operation to pull him out of his despair. Batman, cowl on, ran up the steps to his batmobile. Somewhere Wonder Woman was on a city block, winding up her Lasso of Truth, running like hell to the rescue. Somewhere Peter Parker pulled on his mask and Spider-Man swung through the tall buildings as fast as he could — time was of the essence. From the North Pole, Superman flew down like a jet, scanning the whole of Madison, Wisconsin with his x-ray eyes to find whatever rupture had just happened there. Somewhere Iron Man suited up and made for the sky. In the UK, Harry Potter and his bombastic crew of posh magic-folk mounted broomsticks. Captain America rushed through a crowded city street, his shield up. Maybe he could have made it in time if everything hadn’t gone differently. Maybe. Almost. All of them were too late, though. It wasn’t the thought that counted then and it’s not the thought that counts now. This was an ending. Sad songs go like this. The damage had been done. The damage might never be undone. L— was gone.

In the year and a half I still lived in Madison after I graduated, I lived alone. Most of the roommates I weathered through the pandemic with had moved out of town and I became lonely enough to start talking to the moon.

Something about the pandemic broke me down too, reduced all my aspirations to false American dreams, murky shadows. What the hell would I do with a real job? What would I do in graduate school? Everything felt like a shadow of the old world carried over. Well here I am now. And I still feel broken in a way. I could blame the pandemic but maybe it’s just me. Maybe it took the pandemic to revealed me to myself; maybe it took the pandemic to reveal the world as a hollow bodied guitar still resounding yesterday’s chords making up a song no one believes in anymore.

Inspired by What Kingdom by Fine Grabol; Inspired by Birds by Bruno Schulz

Next week:

i really feel sad for L, lol. but honsetly that feeling of being broken down after the pandemic and opening up for a whole new world after being locked in reality circumastances is so real. i guess we get used to things very easily we ignore their coming conculsions.

The story about L had me paying close attention. Beautiful, very honest. I hope all is well with Helen.