we’ve all been drafted into something that’s rapidly diminishing

after third spaces’ funeral procession, second spaces fall deathly ill

Then he untied the bonds of the king of Babylon and abandoned him in the middle of the desert, where he died of hunger and thirst. Glory to Him who does not die.

- The Two Kings and the Two Labyrinths, Jorge Luis Borges

Who hasn’t woken up one morning, or gone out to eat lunch in the store across the street from their work, and thought to themselves that they’re suddenly and irrevocably something and not nothing like they once were? And who hasn’t been laid off from their work and come face to face with the prospect that they might now be nothing yet again?

At the end of the day, we’re all somethings, and this has been the case since we first organized ourselves into the structures that give our societies meaning, but this self-identification game has become a main staple as the gig economy model took hold and self-marketing became so intimately linked to employment, rent payments, medical insurance, general wellbeing, etc. that to not be a something means to not be self-sufficient in any way.

Ever since the pandemic-era ascendency of online spaces over the social realm, there’s been a slow and steady creep of nothingness into what was once a steadfast real social culture. At the same time, there’s been a slow trickle of AI slop into library systems, signaling that the overwhelming waves of mindless attention junk filling up our online spaces does also, in fact, have real-world implications.

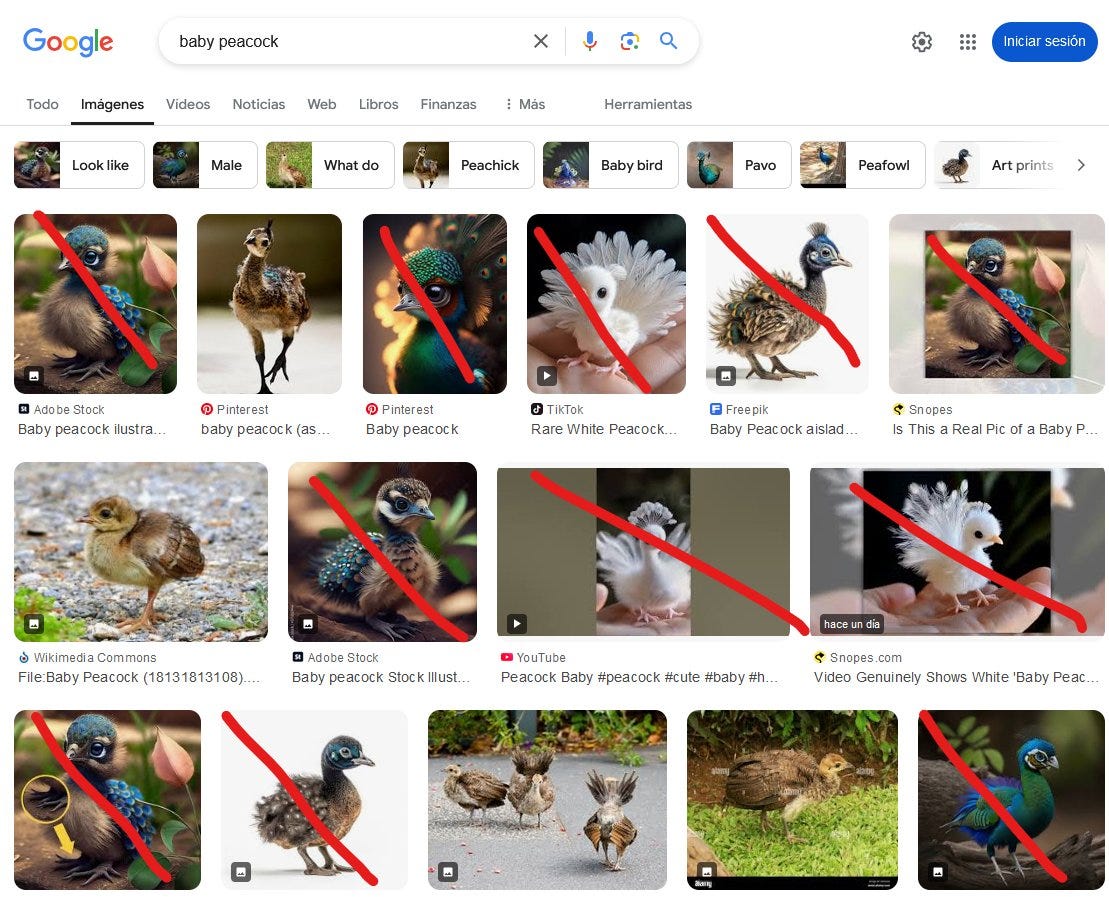

The platforms we exist inside today are more than capable of containing us and who we see ourselves as, — they’re partially made for just this purpse, with Facebook having originally been envisioned as something of a Harvard Yearbook (based on looks), — but these platforms are at the same time also capable of housing a whole lot of what I’ll call here “pleasant nothings”. Just so long as there are eyes to look and ears to be entranced, there are increasing landscapes of slop growing out from the horizons of our Google searches, from our algorithmic feeds through mechanized SEO optimizations and into our media streams.

In other words, the internet has become clouded by what seems like endlessly garish stock photos that have obscured the entire social realm (as has become digitized), so that nothing much can be made out clearly anymore. As

puts it, this will demand a new sort of internet hygiene.We have to revert to more intentional means if we want to be able to conceive of our thoughts through those of others: that means reading intentionally for more than a couple minutes a day, listening to voices we trust (though not to the extent that they become self-proclaimed vanguards to a cause), trusting one another enough to share conversations like breaking loaves of bread with one another and drinking each other’s wine. Most of all this means breathing deeply and not trying, — like I find myself doing all too often, — to snort up digital bite-sized communications.

But while the “sloppification” of online spaces coincides with their gradual “enshittification”, two terms which, like bandages, have been applied onto our collective platform attention economies out of sheer bafflement with the current state of their affairs, we’re at the very same time beginning to be pushed out of our work spaces, those second spaces which secure us our wellbeing.

It’s nothing new, at least on Substack, to announce that we’ve lost our third spaces (those which satisfy a social need) to the pandemic;—but now it seems as if we are also fast losing our second spaces (our workplaces, those which satisfy an individual monetary stability), on a grand scale, to a hackneyed digitized boardroom dream spurred on by a Silicon Valley desperate for anything new to sell to their investors, a Silicon Valley who sees AI as their golden goose, a Silicon Valley who has convinced a great majority of executives in all industries, through private and public means, that their workforces can be almost entirely collapsed into generative algorithms and still function.

Let us not be convinced. Silicon Valley has for the most part manufactured the AI scare into reality. The issue with AGI (their term: Artificial General Intelligence) is that, — I’m going to call it, — it doesn’t exist, or at the very least it doesn’t exist in the way that it’s claimed to. The threat of AGI is manufactured by Silicon Valley. Why? Because if they manufacture fear around a generalized AI which can think on the level of twenty human operators, —again, something I genuinely think is technically impossible at the time of this writing, at least from the people who’s big claim to fame is the Google algorithm, — then it becomes a pressing matter for all of us who are faced with the snuffing out of our jobs and therefore our own livelihood1. Bill Gates’s quote a couple years ago that AGI is the greatest threat to mankind was at the end of the day really just a call for venture dollars and for renewed public attention towards Silicon Valley as the proprietors of “the next big thing” after it’s failing to live up to its own hype and finding anything new or novel since Steve Jobs unveiled the iPhone. And why should we believe Silicon Valley’s takes on anything if their last two “next big things” were the metaverse and NFTs?

But it’s beyond question that Silicon Valley’s empty fearmongering certainly has affected corporate suites who have been slashing jobs with razor blades this past year, dreaming with stars in their eyes about their bottom lines.

Because layoff’s this past year have been massive across the board in major American cities and a rough estimate of 70% of American workers are preparing to be laid off in this coming year. There seems to be much headclutching and bemoaning from those already laid off as they’re thrust suddenly onto their own after having gone through the six or eight years of degrees and skills training to compete against one another for a rapidly diminishing pool of jobs, a rapidly diminishing pool only through which, in the neoliberal work framework that our country rests upon, their self-chosen “something”s can be validated through personal economic stability. And at the very same time as these exiles scrounging for pennies to wash their laundry, they’re watching from a distance as their old desk jobs are performed with no better human acumen than AI meme accounts on instagram. We’re being crushed out, it seems like, of all that we were told mattered in our adult lives, — and worse, we’re being replaced by chatbots while we barely make ends meet.

And the same question remains, that which we should have been been asking ourselves since the very first automotive plant was automated, namely: what was the point of automation if it doesn’t make our lives better? Automation is not a bad thing, per se, — it’s a technology like any other, — but the issue remains that none of its gains are redistributed. They’re simply funneled to the top. This is not a new idea. But it is something we increasingly need to reckon with2.

Forgive me here for a little aside on my personal experience in finding work. “I don’t know what real people do,” I once agonized to two of my close friends who had fledgling careers back when I was just a month or two out from a freshly achieved BA degree in English Literature and finding next no success in finding myself work, “what do all those people even do when they sit behind desks? I can’t understand any of it.”

And I never was able to secure anything appropriately white collar enough to appease my family, — instead I’ve worked at restaurants, and hey, that’s not the worst thing. I’ve found real value in restaurant work. Despite all its (obvious) drawbacks, — the hours, the minute exhaustions, the hectic scheduling, — I’ve found serving tables and the small conversations with thousands of people over the course of two and a half years to be rather rewarding and encouraging towards a general hope for humanity.

Anyways, back to the point at hand. It’s been interesting to watch as people who’ve lived and worked behind those walled gardens of white collar jobs, those which I so yearned for once upon a time, are laid off in such massive numbers that they’ve begun to knock on the doors of food service.

Almost every time I’ve gone in to interview for a serving position over these past couple of months, alongside the usual crowd of twenty-somethings with mullets and piercings, there were always a handful of applicants in their mid to late 30s standing around coyly in full business attire with resumes inside padded pleather portfolios, waiting for their shot at a position where they would be running chicken alfredo from pass to table.

Whenever I spoke with them in that idle way of talking between two hopefuls pining for the same job, it’s almost always been the case that they had been recently laid off from some marketing team, from an IT position, from their finance position in the loop, and that now they had been pushed out they were trying their hand at food service because it seemed less precarious than the white collar jobs which, in the minds of their higher ups, could be easily replaced by a chatbot.

Serving cheeseburgers and fries has become a refuge for those who graduated with safe degrees. Let that sink in. It’s funny in a way.

Food service has always been scorned, — here I’m thinking of the Good Will Hunting line, “and you’ll be serving my kids fries through the drive-thru on our way to a skiing trip,” —but food service is also always going to prioritize the human element; no AI is coming for a proper bartender’s or server’s position. That’s a fact. And that’s not even mentioning that food service is work that’ll likely always be adjusted for inflation so long as the American tipping culture remains intact. It’s really not a bad gig if you have the stamina for it. But I digress.

Now let’s be clear, these waves of mass layoffs, these deathly illnesses of second-spaces in the United States, are not simply a symptom of “progress” or whatever tech companies would prefer to call them, rather they’re a deliberate and petty act of revenge against the employees which make up 90% of their companies. Layoffs in favor of automation is an act of class warfare. Let’s not get this wrong.

Their notion of AI, which is really just elaborate generative software, does not replace people and this will be realized with time, but that mere reality won’t stop their enforcement of their own bourgeois hegemony, — corporate America has long held a real disdain for their underlings which has only been duly amplified by their recent petty wars waged against their employees to get them back into offices after the pandemic, or forcing surveillance software onto their computers, or both, and more!

I don’t think it would be at all remiss to restate this fact: the elimination of jobs across the board in favor of their automation is, rather than “progress for the betterment of mankind,” an aggressive act of vengeance by corporate America against their workers who have in recent years been talking more among themselves about unionizing and attempting to negotiate for themselves,—here is their chance to sweep away their entire staffs made up of the humans who have always made problems for their bottom lines.

This way they can spit in the faces, cut themselves off from their human laborers, say “it’s what they deserve for asking too much of us,” behind closed board room doors, and ghost like an soon-to-be ex who’s been hiding their resentment of their partner for years, even decades.

They’ve put up with the dumb apes of their workforce long enough. Their ascension has arrived. They’ve waited long enough. Now the 0.5% holding 97% of the wealth in this country has what seems to be a golden opportunity to detach completely from the 99.5% of us underlings, leaving all of us to a pure abject poverty.

They’ve dreamt of this moment far too long to thumb their nose at AI’s lack of actual ability, — because the promise they’ve been sold is that soon enough, some sort of AGI will have the ability that a human has, that 100 humans have, and since their whole business philosophy demands that they get ahead while they can, they’re rushing to integrate before such a thing exists simply because it’s been promised by Silicon Valley.

And besides that, replacing human operators with the “pleasant nothingness” of generative AI is quite simply an evil thing to do, — and I don’t use that term lightly, — especially coming out of the past century’s project of putting every individual’s sense of self-worth into their self-marketing themselves as a “something” which can compete in the market economy with other human “somethings.” They pulled the rug out from underneath us. Never did we suspect that they would use pleasant nothings to oust us all like they did, but of course Wall Street has no moral bar so low that they won’t crawl on their stomachs.

The entire American economy, for anyone under the age of 40 at least, is going the way of an Amazon warehouse. I’ve said this before and I still believe it’s true. The incentives are still there; and nothing’s being done to deter them. Both candidates running for the presidency during this round of “most important election of our lifetime” have signaled that they’ll only exacerbate these issues. If employees can’t present themselves to their masters as purely mechanical cogs, then, well, they’ll be replaced by actual purely mechanical cogs, those which cannot negotiate for themselves and cannot have any sort of individual volition. This is such a win for our masters that it hurts to even think about. And we’re too focused on Pop Crave to even care.

And as for you and me, our lived reality will continue to get worse as more is automated and interlaced with systems that are as surface-level as they are haplessly non-human.

Think of the 2021 incident in the Suez Canal, think of the derailment in Palestine, Ohio. These incidents occurred because regulations and federal oversight had been chopped in half because of intense lobbying pressures. The trains had become longer than ever, with less operators than ever; shipping vessels had begun their routes with less and less oversight, — and certainly it should be no surprise to us now, in this age of enshittification, that these real world incidents will happen more and more going forwards into the twenty-first century, our century, tied up intimately with the recklessness that’s brought upon us the seemingly irreversible climate catastrophe that’s currently wiping clean the lower Eastern seaboard.

This is the future we’re headed towards as generative software is used for things beyond sending marketing emails for Rolling Stone, — and is there anyone in any position of power signaling any sort of alarm? Of course not, because again: they’ve been waiting for this moment of ascendency from their human workforces for far too long to relent now.

The self-proclaimed guardians of our online spaces have seemed to lay down and accept the slop as contributing well enough to their platform’s net worths (while trying really hard to become likable), and we shouldn’t be too surprised by this, — but then where’s federal oversight? Shouldn’t something be done? What Powers That Be decreed this as acceptable in our newly digitized public realm? Besides the well-known fact that our elected officials in the United States are well past their expiration dates for knowing anything that’s going on at all in their country, I’m going to posit that perhaps the straw that broke the camel’s back in all this was the #FreePalestine movement. A mild hesitancy towards legislating the slop out of the internet has become a complete afterthought because endless nonsense doesn’t go as explicitly against the wishes of American empire as would a cleaned up internet, and in an internet filled with nonsense, all criticisms of America’s proxy state can be dismissed as part of the general detriment.

Imagine the discourse without all the slop; imagine what would happen if real world videos of the genocide in Palestine began to circulate again? And to a certain extent, too, there’s a sort of feeling I think amongst both Silicon Valley’s owners and Washington’s owners that the platforms where young people live their social lives deserves the slop, because the politics of Gen-Z and younger millennials don’t align with those of the American imperial project.

Anyways, the real takeaway of all this is, in my mind: Generative AI’s usage is going to be so detrimental to all of us because it’s being applied through class spite and it’s being called technological progress.

I’ve seen Substack described as the refugee camp of the internet and certainly that will only become more true with time. Mass layoffs in journalism end with more career writers/journalist coming to these orange-and-white shores. Mass degradations in the quality of instagram, facebook, and twitter will lead more content creators here.

As with any refugee camps grown out over time, the developing factions will become more pronounced, — between the girlhood essayists and the libertarian iFunny accounts, between the casual thinkpiece writers (I guess I’m included in this) and the industry-vetted journalists, between the fashion writers and the self-proclaimed poets, — but this, in my eyes, just shows that there’s quite an interesting deck of cards here on Substack in an era of the internet where nothing seems quite as interesting as it used to. That’s to say, I’m long on Substack, — I would bet on it if I could (but if Substack the corporation ever does an IPO event, I’m moving to beehiiv) — I think this is the place to be.

But let’s not take this place for a proper replacement to the real. We need real world institutions to support ourselves and each other, and we need a life outside the realm of the internet. But all of our real world spaces are rapidly diminishing. Can’t you feel it? We’re losing our second spaces rapidly like we lost our third spaces, and soon all we’ll have left to us is our own apartments, our first spaces, until we lose those too, — if we haven’t lost those already.

Everything we have is being taken away from us by the richest in this country; everything we have’s being funneled from us through the most mid of Web2.0 platforms. It would be funny if it wasn’t so dire. Even if you’re not looking, can’t you feel the disappearance? Can’t you tell that your eye is catching less and less of something and more of nothing? The replacing of what was once a bountiful something with an endless, empty pleasant nothingness?

This isn’t a consequence of our individual actions. We’ve done nothing to deserve any of this. What it may be is a blind adherence to an invisible hand of the market in accordance to a system of affairs four centuries old which had in itself, hidden away in its shadows, the trappings of medieval feudalism which hasn’t gone away, gone rancid with the emergence of the internet and its immediacy wherein capital, — if it can be considered a sentient entity with its own volition, selectively choosing humans as its moronish, bouncing champions to channel its will through, — could finally detach itself entirely from the pesky humans who lived on its market flows like mosquitos on a bull.

That’s all to say: Capital has had us completely in its bondage since the American century began; and now it seems intent to leave us to starve forever in these backlit isolated cages it has created for us.

I want to cry out, “if only we looked around us!”, to every person I see on the street, to every person in my subscriber count (I suppose I’m doing just that right now), to every person in my contacts, but I worry deeply that if we were to look up from our phones for even the slightest of seconds we’d only see a very somber state of affairs, and then we’d open tiktok and swipe up.

Quick links: Sticky Humans in a Post AGI World by

; The internet is obsessed with watching pretty girls eat by ; the worst thing to be on substack is a substacker by ; The snoopy fan account political war by ; The End of Small Thinking by ; The Internet's AI Slop Problem Is Only Going to Get Worse byP.S. Any grammatical errors are entirely intentional, because, — hey, — I don’t have an editor for these posts, and if I forget something I feel completely comfortable calling that an intentional forgetting.

If only there was a political theory set on separating our jobs from our livelihoods so that one doesn’t entail the other… What on earth could that be?… Certainly it hasn’t been suppressed by economic and military might, on a global scale, for over a hundred years… Oh wait, it has… Anyways, I digress.

For more on this, check out Srnicek and Williams’ brilliant and appropriately radical book Inventing the Future: Post-capitalism and a World without Work

reading this at the office on company time while pretending to work… as god intended

I saw the greatest minds of my generation driven mad trying to get people to click ads 1.4% more than they did last quarter.

Neoliberal vengeance for 2020's Great Resignation won't stop until every single worker feels as precarious as we did in Spring 2022.